Utopia, Depravity and Trauma in Weimar Prints

Exhibition Review published in The Double Negative

This piece was published in The Double Negative

With my art historian goggles on, walking around this exhibition of Expressionist prints is like entering a posh deli with a limitless gift card. The delicacies include Picasso’s Le Repas Frugal, Much’s In the Male Brain, and Egon Schiele’s Sorrow, the only print by Schiele held in a British public collection. With my empathetic human goggles on, it is a deeply affecting show that demonstrates the idiosyncrasies of individual artistic reactions to great trauma and the disturbing polarities of experiences in Weimar Germany, oscillating between utopic scenes of peace, sexually charged depravity and extreme poverty, destruction and loss.

Picasso, Le Repas Frugal

The works hold their own in this show as the curators step back, offering information on each print but not attempting to string together much of a coherent narrative of this complex and turbulent period of German history. It is a slight misnomer to title it German Revolution as the exhibition includes works spanning about 40 years, from before the turn of the century right up until the late thirties. They are right to pull out threads of themes but it would be an impossible task in one small exhibition to tell how these artists all relate to one another in their various secessions and avant-garde groups. German Expressionism is so rich for just that, it encompasses a historically specific set of anxieties and sentiments more than a single artistic style or language. This exhibition really manages to demonstrate this scope of artistic reactions and interventions in one of the most politically and socially tumultuous eras of Germany’s history.

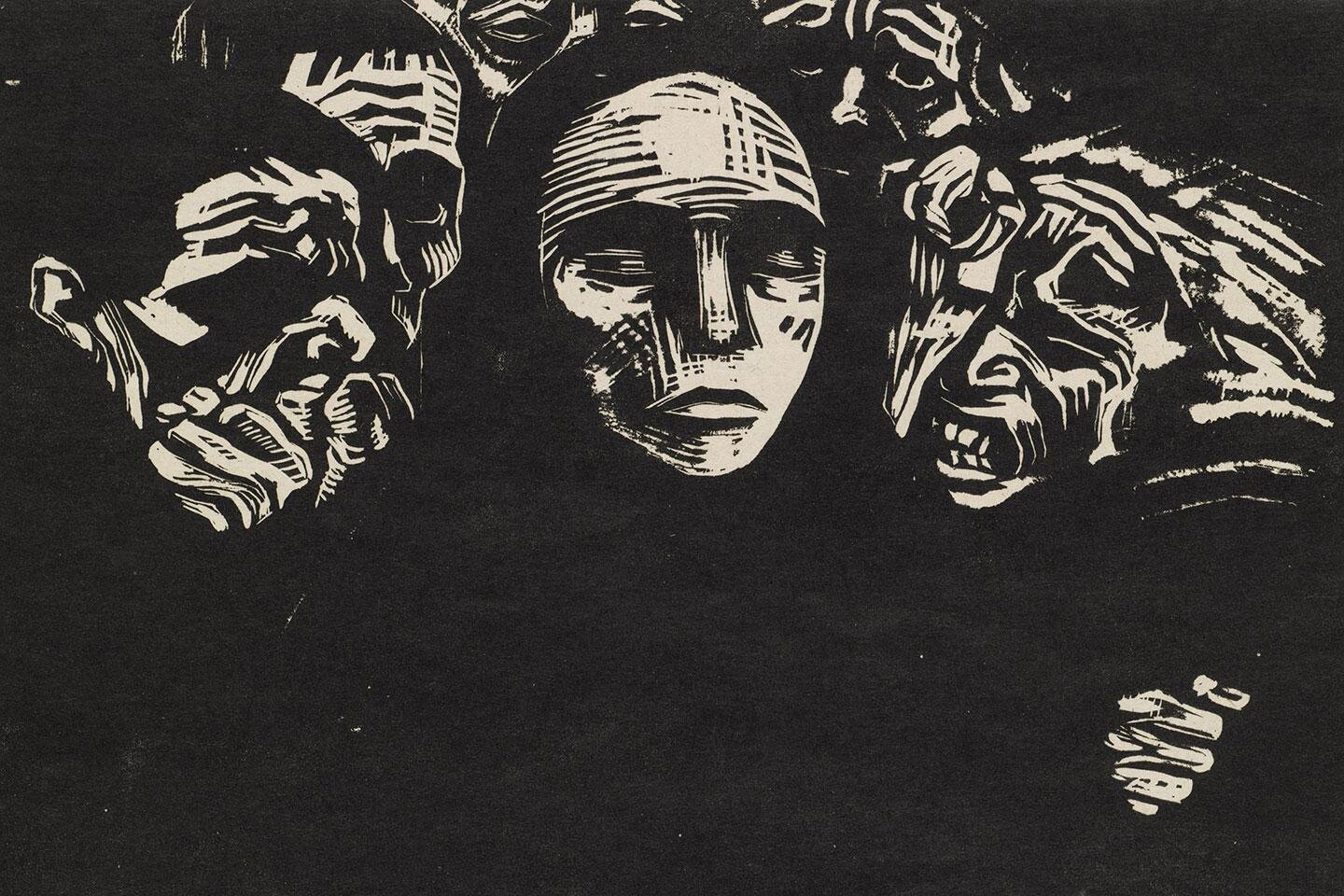

Comprised mainly of lithographs, woodblock prints and drypoint etchings, we get to see how differently artists like Max Beckmann, Karl Schmidtt Rotluff, George Grosz and Kathe Kollwitz wielded line in their mediums as a means of directly conveying the emotional weight of life around them. In Grosz’s Fit for Garrison Duty we have a taste of his cynical wit as he found a dark humour in pointing out the hypocrisies and corruption of all strata in German society. Here we see an old soldier approaching us, balls sagging through his breeches with a neck as thick as his head like a prize bull at a fair - a far cry from something like Max Backmann’s The Martyrdom of one year earlier. In this disturbing lithograph you’ll see Rosa Luxembourg, a revolutionary leader who was killed as part of the brutal suppression of the socialst uprising, arms outstretched being carried away by soldiers who jab and taunt her with their rifles, grope her breasts and laugh demonically. Different again, Otto Dix’s Acrobats of 1921 turns our gaze towards people from the entertainment industry during the interwar period, in all its glitz and grime, the woman looking at us, breasts bulging out of her corset and the wonderful detail of a flaming heart tattoo on her thigh. Away from the dancing, sex and jazz, we then get Kollwitz’s deeply sad portraits of the emaciated poor. It was good to see so much Kollwitz and other female artists taking their rightful place in this exhibition, with the inclusion of Paula Modersohn Becker and Gabriele Munter. Their works provided crucial insight into the reality of female experiences as portrayed by women, rather than the sometimes reductive depictions of women by their male counterparts.

Otto Dix, Acrobats

I was slightly disappointed in the exhibition’s handling of the thorny issue around cultural appropriation. It was acknowledged that many of the Expressionists who traveled to Palau (a German colony at the time) produced “idealised images that do not reflect the harsh struggle of the local population to survive in the face of the impact of long term colonial rule.” However, more could have been said to offer a critique of the artists’ essentialist interpretation of objects in the Ethnological museums, and their appropriation of a “rough” “primitive” style to convey a raw and spiritual artistic expression. We know by now that even if this was normal for the time, it can’t go unsaid when displaying the works in our current world.

I could go on about more of the fascinating treasures included in the exhibition, but I will leave the rest for you, dear reader, to explore with your own eyes and mind. I very much recommend seeing it in the flesh if you can, but be warned, you will need your emotional resilience that day.